What’s the diagnosis?

A gradually enlarging nodule on the finger

Case presentation

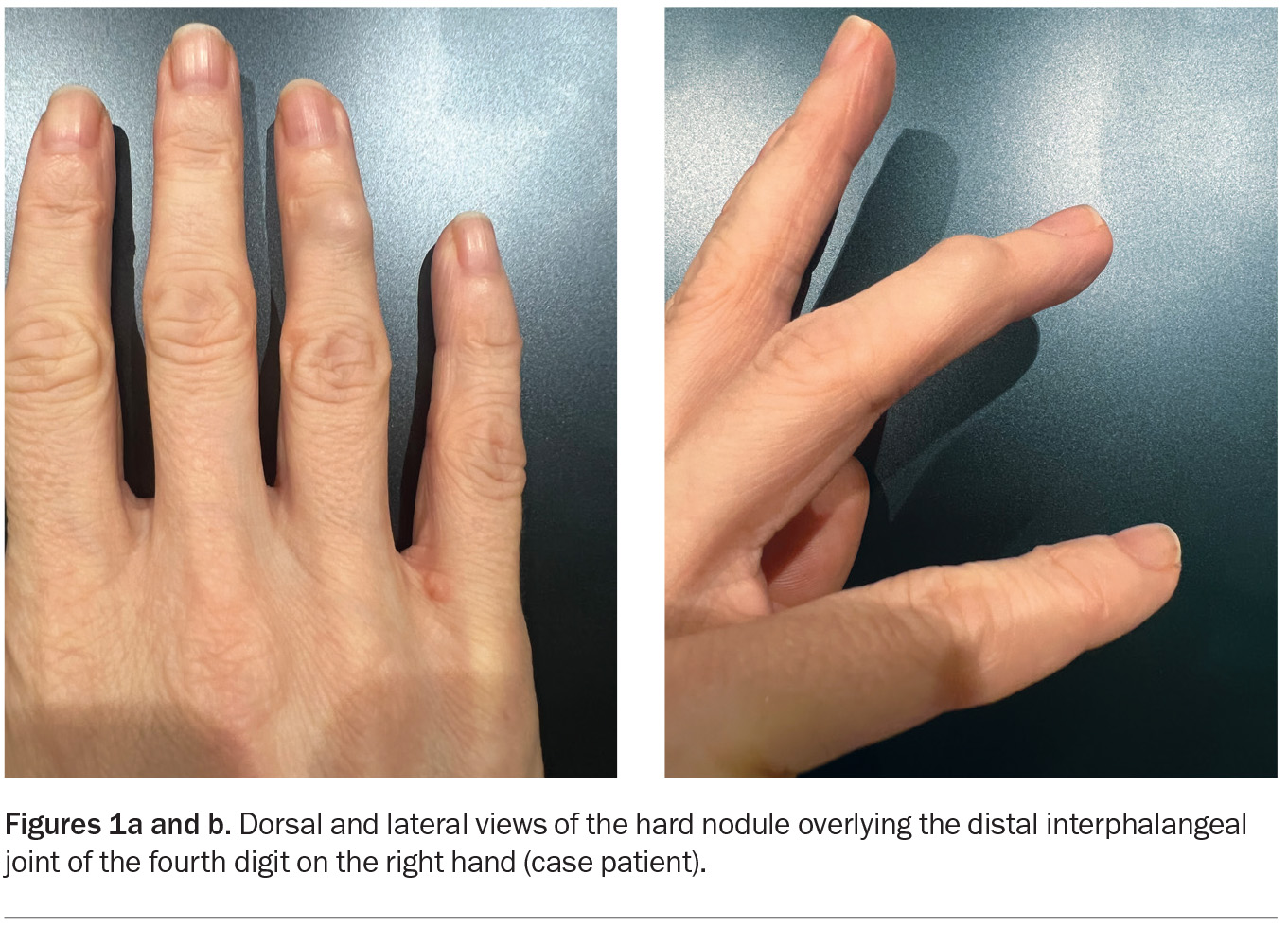

A 40-year-old woman presents with a firm nodule on her right ring finger that has been enlarging over a four-month period (Figures 1a and b). The lesion is nontender and is not associated with a reduced range of movement. She is a nonsmoker and drinks alcohol occasionally.

On examination, a hard nodule, about 1 cm in diameter, is observed overlying the distal interphalangeal joint of the fourth digit on the patient’s right hand. The skin overlying the nodule is stretched but appears otherwise normal. The neurovasculature of the finger is intact and capillary refill time is normal. An x-ray is performed, which does not show features of arthritis.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Digital myxoid cyst

A digital myxoid cyst is a benign, fluid-filled nodule that is typically located on the dorsal aspect of the distal phalanx or overlying the distal interphalangeal joint. The exact aetiology is not known, but it has been proposed to be an outpouching of the synovial lining.1 The cyst is usually seen in patients over the age of 50 years and associated with osteoarthritis of the joint and its symptoms, such as pain and stiffness, and deformity.

Clinically, a digital myxoid cyst appears as a shiny papule that may be semi-translucent. There is variation in colour, ranging from skin-coloured to reddish, and in size, ranging from a few millimetres to over a centimetre in diameter. The cyst is usually not painful but may be tender when knocked. If located close to the nailbed, it may cause a groove along the length of the nail by disrupting the nail matrix.2

The diagnosis of a digital myxoid cyst is primarily clinical. Aspiration of the contents, if conducted, reveals a clear, viscous fluid that is sometimes tinged with blood.3 In some cases, an x-ray can be helpful to assess for underlying osteoarthritic changes.

For the case patient, the hardness of the nodule was not consistent with a diagnosis of a digital myxoid cyst. She had no history of osteoarthritis and x-ray did not reveal any osteoarthritic features, such as joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation or subchondral sclerosis. She was also younger than a typical patient with a digital myxoid cyst.

Heberden node

A Heberden node is a hard, bony swelling of the distal interphalangeal joint. It is a hallmark of osteoarthritis, resulting from chronic degenerative changes in the joint cartilage and ligaments and subsequent bone remodelling.4 There is a genetic predisposition to the development of the nodes, which are common in middle-aged or older individuals.5 The nodes are seen in more than 60% of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee.6

Heberden nodes are usually painless but often associated with underlying symptoms of osteoarthritis, including pain, stiffness and reduced range of motion. Furthermore, friction-induced capsular rupture and synovial leakage can occur, leading to inflammation of the nodes and causing an erythematous, swollen appearance and increasing pain.

Heberden nodes are usually diagnosed clinically. Radiographic imaging can be useful to confirm the presence of osteoarthritis.7

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. She did not have any symptoms or radiographic findings of osteoarthritis. In addition, the lesion had developed over a few months, and was continuing to grow, which was not consistent with a Heberden node, which usually grows more slowly over a longer period of time.

Rheumatoid nodule

Rheumatoid nodules are the most common dermatological manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis, a systemic autoimmune condition characterised by chronic inflammatory arthritis and extra-articular involvement. The nodules occur in about one-quarter of patients with rheumatoid arthritis; they are more common in those with longstanding severe disease and in those who test seropositive for rheumatoid factor or anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies.8,9 Rheumatoid nodules are most frequently observed in women who are middle-aged and older, in whom the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis is higher. The use of methotrexate to treat rheumatoid arthritis is known to accelerate the growth and formation of rheumatoid nodules, which is known as methotrexate nodulosis.10

Rheumatoid nodules can affect any area of the body, especially sites of repeated trauma or pressure. They are most often found adjacent to the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hands, and the extensor surface of the elbow.8 They appear as well-demarcated, flesh-coloured, firm, subcutaneous nodules that are usually painless, nontender and mobile. There is variation in size, from a few millimetres to more than 10 centimetres in diameter.

A rheumatoid nodule is usually diagnosed clinically on the basis of the characteristic appearance in patients with known rheumatoid arthritis. Biopsy is not often necessary, but if performed, a histological assessment will reveal central necrobiosis, stromal fibrosis and palisading histiocytes.11

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, who did not have a history of rheumatoid arthritis.

Gouty tophus

A gouty tophus is a deposit of monosodium urate crystals in the soft tissues of patients with chronic gout, a metabolic disorder characterised by hyperuricaemia and recurrent episodes of acute arthritis. The deposits result from prolonged elevation of uric acid levels in the blood, which leads to precipitation of urate crystals in various tissues, including cartilage, bone, joints, tendons and skin.12 Gouty tophi are considered a late complication of untreated gout and generally develop around 10 years after the initial attack of gout. Rarely, however, a tophus can develop without previous episode of acute gouty arthritis.13

Gouty tophi can occur anywhere on the body, but the most common sites are the fingers and helix of the ear.14 They appear as firm nodules that contain a chalky, white, paste-like substance. The skin overlying the tophus may appear stretched and shiny. The nodules are generally nontender but can cause pain and inflammation, especially if they compress surrounding tissues or joints.

A gouty tophus is usually a clinical diagnosis in a patient who has a history of gout and raised serum levels of uric acid. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy reveals monosodium urate crystals under polarised light microscopy.12

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient, who did not have a history of gout. The nodule on her finger was not painful and did not contain a white pasty substance.

Tenosynovial giant cell tumour

This is the correct diagnosis. A tenosynovial giant cell tumour (GCT) is a rare soft-tissue tumour that is generally benign but has potential to be locally aggressive. It arises from the synovial lining of tendon sheaths, bursae or joints. The aetiology is not fully understood but is thought to involve genetic mutations that lead to abnormal synovial cell proliferation.15 Tenosynovial GCTs typically affect adults between the ages of 30 and 50 years and are slightly more common in women than men.16

Tenosynovial GCTs are classified as localised or diffuse. The localised subtype typically presents as a slow-growing, painless, firm nodule, most commonly on the fingers and wrist. The diffuse subtype presents as a larger mass, most commonly affecting larger joints such as the hip, knee, ankle or wrist, and is usually associated with significant joint pain, swelling and functional impairment.17 The diffuse subtype tends to be more aggressive, with potential to infiltrate surrounding tissues.

A tenosynovial GCT is diagnosed on the basis of a combination of clinical examination findings, imaging results (x-ray, ultrasound and/or MRI) and histopathological analysis. On imaging, a localised tenosynovial GCT usually appears as a well-circumscribed nodule confined to the tendon sheath or joint capsule. In contrast, a diffuse tenosynovial GCT appears as a more extensive, infiltrative mass with ill-defined borders and, in some cases, associated joint effusion and bone erosion.17 Histopathology of tenosynovial GCTs reveals large histiocytoid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, scattered multinucleated giant cells and, in most cases, small clusters of lipid-laden cells and hemosiderin deposition.18

Management

Surgical excision is the mainstay of treatment for all tenosynovial GCTs. The extent of surgery depends on the subtype, size and location of the tumour: generally, local excision suffices for the localised subtype and complete synovectomy is required for the diffuse subtype.19,20 Adjuvant radiotherapy may be employed in some cases. The reported rates of recurrence are 0 to 15% for the localised subtype and 21 to 52% for the diffuse subtype.17 Metastasis is very rare, with only a few case reports in the literature.21

Outcome

Further imaging was arranged for the case patient. An ultrasound revealed a mass connected to the synovium, without bony destruction, which supported the diagnosis of a localised tenosynovial GCT. The patient underwent local surgical excision by a hand surgeon to remove the nodule. Histopathological analysis of the lesion was performed and revealed multinucleated giant cells, which confirmed the diagnosis. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Eaton RG, Dobranski AI, Littler JW. Marginal osteophyte excision in treatment of mucous cysts.

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1973; 55: 570-574.

2. Lin Y-C, Wu Y-H, Scher RK. Nail changes and association of osteoarthritis in digital myxoid cyst. Dermatol Surgery 2008; 34: 364-369.

3. De Berker D. Digital myxoid cysts: ganglia of the distal interphalangeal joint. In: Baran RL. Advances in nail disease and management. Cham Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2021: pp. 19-31.

4. McGonagle D, Tan A, Grainger A, Benjamin M. Heberden’s nodes and what Heberden could not see: the pivotal role of ligaments in the pathogenesis of early nodal osteoarthritis and beyond. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47: 1278-1285.

5. Irlenbusch U, Schäller T. Investigations in generalized osteoarthritis. Part 1: genetic study of Heberden’s nodes. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2006; 14: 423-427.

6. Kumar NM, Hafezi-Nejad N, Guermazi A, et al. Association of quantitative and topographic assessment of Heberden’s nodes with knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018; 70: 1234-1239.

7. Swagerty DL Jr, Hellinger D. Radiographic assessment of osteoarthritis. Am Fam Physician 2001; 64: 279-287.

8. Ziemer M, Müller AK, Hein G, Oelzner P, Elsner P. Incidence and classification of cutaneous manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2016; 14: 1237-1246.

9. Tilstra JS, Lienesch DW. Rheumatoid nodules. Dermatol Clin 2015; 33: 361-371.

10. Jang KA, Choi JH, Moon KC, Yoo B, Sung KJ, Koh JK. Methotrexate nodulosis. J Dermatol 1999; 26: 460-464.

11. Bang S, Kim Y, Jang K, Paik SS, Shin S-J. Clinico-pathologic features of rheumatoid nodules: a retrospective analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2019; 38: 3041-3048.

12. Chhana A, Dalbeth N. The gouty tophus: a review. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2015; 17: 1-9.

13. Koley S, Salodkar A, Choudhary S, Bhake A, Singhania K, Choudhury M. Tophi as first manifestation of gout. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010; 76: 393-396.

14. Angalla R, Mounir A, Driouich S, Abourazzak F, Harzy T. Chronic tophaceous gout. QJM 2016; 109: 681-682.

15. Robert M, Farese H, Miossec P. Update on teno-synovial giant cell tumor, an inflammatory arthritis with neoplastic features. Front Immunol 2022; 13: 820046.

16. Ehrenstein V, Andersen SL, Qazi I, et al. Teno-synovial giant cell tumor: incidence, prevalence, patient characteristics, and recurrence. A registry-based cohort study in Denmark. J Rheumatol 2017; 44: 1476-1483.

17. Gouin F, Noailles T. Localized and diffuse forms of tenosynovial giant cell tumor (formerly giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath and pigmented villonodular synovitis). Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017; 103: S91-S97.

18. Lucas DR. Tenosynovial giant cell tumor: case report and review. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136: 901-906.

19. Staals EL, Ferrari S, Donati DM, Palmerini E. Diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumour: current treatment concepts and future perspectives. Eur J Cancer 2016; 63: 34-40.

20. Kitagawa Y, Takai S. Optimal treatment for tenosynovial giant cell tumor of the hand. J Nippon Med Sch 2020; 87: 184-190.

21. Asano N, Yoshida A, Kobayashi E, Yamaguchi T, Kawai A. Multiple metastases from histologically benign intraarticular diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumor: a case report. Hum Pathol 2014; 45: 2355-2358.

Skin lesions