What’s the diagnosis?

Persistent scaly plaques on the hands and feet

Case presentation

A 44-year-old man presents with scaly plaques on his hands and hyperkeratotic plaques with painful fissures on his feet (Figure 1a to d). The plaques are well demarcated and mildly erythematous. He has suffered for more than two decades from the lesions, which have been resistant to treatment with emollients and topical corticosteroids. Antifungal medications have not been effective.

The patient has a history of obesity, hypertension and dyslipidaemia. He is a current smoker. There is no family history of similar skin disease.

On examination, scaly erythematous plaques with deep fissures are observed on the palmar surface of the patient’s fingers. Nail pitting and subungual hyperkeratosis can also be seen. Thick hyperkeratotic plaques with deep fissures are present on the plantar surfaces of both feet.

Differential diagnoses

Conditions to consider among the differential diagnoses include the following.

Dermatophyte infections

Dermatophyte infections, commonly referred to as tinea or ringworm, are superficial infections caused by keratinophilic fungi. The most common pathogens are from the Trichophyton, Microsporum and Epidermophyton genera.1 These fungi thrive in keratinised tissues, including the skin, hair and nails, leading to a variety of clinical manifestations depending on the affected site. Transmission can occur directly by contact with infected individuals or animals or indirectly via soil or fomites.2 Epidemiologically, dermatophyte infections are highly prevalent worldwide, with increased incidence in warm, humid climates.3 Risk factors include communal living, poor hygiene, occupational exposure, excessive sweating, occlusive footwear and immunosuppression.4

Clinically, dermatophyte infections present with annular, erythematous, scaly plaques. An advancing active border with central clearing distinguishes the condition from other papulosquamous disorders. Dermatophyte infections affecting the hand (tinea manuum) and foot (tinea pedis) often appear as hyperkeratotic, scaly eruptions with a unilateral predilection. Trichophyton rubrum is the most common culprit in chronic and recalcitrant cases.2

A suspected dermatophyte infection can be confirmed by potassium hydroxide (KOH) microscopy demonstrating septate hyphae. Wood’s lamp examination and fungal culture can be used to help rule out conditions, such as pityriasis versicolor, and can be useful in challenging cases.1

For the case patient, a dermatophyte infection was a worthwhile consideration, but the scaling and sharply demarcated border of the plaques and deep fissures, together with the history of failed antifungal treatment, were suggestive of a different condition. In addition, his long history of the lesions and the bilateral involvement of both hands and feet would not be typical of this diagnosis.

Palmoplantar keratodermas

Keratodermas are a heterogeneous group of disorders that are characterised by excessive thickening of the epidermis, most commonly affecting the palms and soles. They can be hereditary or acquired. The acquired forms typically present later on in life and may be secondary to systemic disease (myxoedema or hypothyroidism) or inflammatory skin disorders and associated with pathogens (fungal infections), medications (targeted kinase inhibitors), exposure to chemicals (arsenic, chlorinated hydrocarbons) or other environmental triggers.5-7 Lesions are classified according to epidermal involvement as diffuse, focal or punctate.6

Clinically, keratodermas present as hyperkeratotic, yellowish plaques or diffuse thickening of the palms and soles, often accompanied by tenderness and fissures. Some lesions exhibit well-demarcated scaling, erythema or involvement beyond the acral surfaces.8 Diagnosis is primarily clinical and supplemented by histopathology if needed, which reveals epidermal hyperplasia, hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. If hereditary palmoplantar keratoderma is suspected, referral for genetic testing is recommended for identification of the causative variant.9

This was not the correct diagnosis for the case patient. A well demarcated plaque with an inflammatory border is not common in this condition. Further, subungual hyperkeratosis is not often seen. A diagnosis of palmoplantar keratodermas would be more likely if the lesions were isolated to pressure points or he had a family history of similar lesions.

Dyshidrotic eczema

Dyshidrotic eczema (pompholyx) is a chronic vesiculobullous dermatitis that affects the palms, soles and lateral aspects of the fingers. The clinical presentation is distinctive: clusters of intensely pruritic, deep-seated, fluid-filled vesicles on the palms and fingers and sometimes the soles. Over time, the lesions can rupture, leading to peeling, scaling and fissuring that can be painful and functionally impairing.10 Unlike other eczematous conditions, dyshidrotic eczema is typically not erythematous in the early stages, with inflammation becoming prominent only when vesicles rupture or secondary infection occurs.11

The aetiology of dyshidrotic eczema remains unclear, but it is thought to involve a combination of genetic factors, hypersensitivity reactions, environmental triggers and disruptions in skin barrier function.11 Common exacerbating factors include stress, allergic contact dermatitis (e.g. nickel or cobalt allergy), hyperhidrosis and excessive hand washing. The condition is more prevalent in warmer climates (and during warmer months), and some individuals experience flares in response to ultraviolet radiation exposure; conversely, cold weather can cause skin dryness as well as blisters and flares. Dyshidrotic eczema may also be triggered by fungal infections and cause vesicular eruptions that are distant from the primary site of infection.12

The diagnosis of dyshidrotic eczema is clinical, based on the presence of characteristic recurrent lesions. Patch testing may be performed to rule out allergic contact dermatitis, especially in cases linked to nickel or cobalt sensitivity.

For the case patient, the thick scale and well-demarcated borders of the plaques and nail changes were not consistent with a diagnosis of dyshidrotic eczema. In addition, he did not have a history of the characteristic fluid-filled vesicles.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is a chronic inflammatory immune-mediated disorder that tends to affect the skin and mucous membranes but may involve the nails and scalp. The aetiology remains unknown, but it is believed to be a T-cell-mediated autoimmune reaction targeting basal keratinocytes and affecting stratified squamous epithelia.13 Lichen planus affects between 0.1 and 1% of the population, with a slight female predominance, and peak incidence between 30 and 60 years of age.14

Various triggers have been implicated in lichen planus, including viral infections (especially hepatitis C), certain medications (e.g. NSAIDs, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors) and contact allergens.13,15 The condition has also been associated with graft-versus-host disease and underlying malignancies.16 It is not directly hereditary but affected individuals appear to have a genetic predisposition.17 The condition is not infectious.

The clinical presentation of lichen planus depends on the site involved and morphology of lesions. The cutaneous variant classically presents as violaceous, flat-topped papules with fine white reticulations (Wickham striae), most commonly on the flexor surfaces of the wrists, forearms, ankles and lower back. Pruritus is often severe. When involving the palms and soles, lichen planus may appear as hyperkeratotic plaques with less pronounced violaceous discoloration. Oral lichen planus, the most common mucosal variant, manifests as Wickham striae or painful erosions on the buccal mucosa. Nail involvement may lead to longitudinal ridging, thinning or pterygium formation.14,18

The diagnosis of lichen planus is primarily clinical but a skin biopsy with histopathological examination is often performed for confirmation. Key findings include hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, saw-tooth rete ridges, a dense band-like lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermoepidermal junction and apoptotic keratinocytes (Civatte bodies). Other investigations include KOH testing and direct immunofluorescence microscopy, which may show fibrinogen deposits at the basement membrane zone.19

For the case patient, the presence of well-demarcated erythematous plaques and nail pitting were not consistent with a diagnosis of lichen planus.

Palmoplantar psoriasis

This is the correct diagnosis. Palmoplantar psoriasis, a chronic variant of psoriasis that specifically affects the palms of the hands and soles of the feet, accounts for about 3 to 4% of all cases of psoriasis.20 The disease course is typically chronic and relapsing, with periods of exacerbation and remission.21 Palmoplantar psoriasis can occur in isolation or alongside psoriasis affecting other body areas; an estimated 10 to 25% of individuals with palmoplantar psoriasis have chronic plaque psoriasis.21 Recognising coexisting lesions elsewhere may support the diagnosis and guide treatment decisions.

Palmoplantar psoriasis can manifest as thickened, hyperkeratotic skin or sterile pustules or a combination of both.22 Typically, the central parts of the palms and/or soles are symmetrically involved, often with associated pain, burning sensation and itch.22 The plaques are well demarcated, thickened and erythematous with overlying scale. Patients may present with painful fissures that impact daily activities and quality of life. Nail involvement, such as pitting, onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis, is common and can help differentiate psoriasis from other common conditions.

Palmoplantar psoriasis results from an interplay on genetic, immune and environmental factors. It is associated with dysregulation of the T helper (Th) 1 and Th17 immune pathways, and the HLA-Cw6 allele is strongly associated with disease.23 Infections, psychological stress, smoking and trauma can precipitate or exacerbate the condition.23

Investigations

The diagnosis of palmoplantar psoriasis is primarily clinical, based on the characteristic appearance and distribution of lesions. A biopsy is not usually needed, but histopathological findings (epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, Munro microabscesses, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration) can help differentiate palmoplantar psoriasis from mimics. Further investigations may include a skin scraping for fungal KOH microscopy. Screening tests for metabolic syndromes may be appropriate because patients with psoriasis are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease.22

Management

Management of psoriasis, including the palmoplantar variant, is tailored to disease severity and patient preference. Lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation and weight management, are crucial in improving disease outcomes and reducing comorbidities.24

For mild to moderate disease, topical corticosteroids are first-line therapy. Patients should be instructed on application frequency (once or twice daily) and use of the fingertip unit to measure the quantity of cream or ointment (one fingertip unit covers about 2% of body surface area).25 Potency selection depends on the area to be treated. Low-potency corticosteroids (e.g. hydrocortisone 1%) are required for more delicate areas, such as the face and genitals, whereas mid- to-high potency agents (e.g. betamethasone and clobetasol) are used on the trunk and extremities.26 High-potency corticosteroids should be used with caution and typically for no more than four to six weeks.

For patients who have hyperkeratotic psoriasis of the palms and soles, topical corticosteroid treatment is often combined with calcipotriol, a vitamin D analogue, which inhibits keratinocyte proliferation. Use of a vitamin D analogue together with topical corticosteroids has been shown to be more effective than either treatment alone.26,27

Keratolytics (e.g. urea 10 to 30%, salicylic acid 10 to 20%) are often used to soften and remove thick scale, enhancing the penetration of topical treatments.24 These are particularly useful for patients with palmoplantar psoriasis who have thick plaques. Coal tar preparations, which are also frequently added to topical therapy to help treat scaling, itch and inflammation, can be compounded with keratolytics or found in shampoos available over-the-counter. Both coal tar and keratolytics are used in combination with other topical treatments; application is typically recommended in the morning if other topical treatments (e.g. topical corticosteroids, calcipotriol) are applied at night.28

For patients who have pustular psoriasis of the palms and soles, betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% ointment or mometasone furoate 0.1% ointment, applied once daily until skin is clear (usually for two to six weeks), is recommended as initial treatment.28

Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy, which works by inhibiting the immune and inflammatory pathways in the skin, is a valuable option for patients who have more widespread disease, with two or three sessions per week generally required for a few months. Use of acitretin, a vitamin A derivative, in combination with phototherapy increases the efficiency of treatment.28,29

For patients with more severe psoriasis or lesions that are refractory to initial therapy, systemic treatment may be required. Options include conventional (nonbiologic) therapies such as acitretin (alone or in combination with phototherapy), ciclosporin and methotrexate.30 In addition, two oral small-molecule therapies, apremilast and deucravacitinib, have recently become available.

Apremilast, a phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor, has minimal contraindications to use and is a good alternative when methotrexate and acitretin are contraindicated. Apremilast is generally well tolerated, although gastrointestinal upset (diarrhoea, nausea) and respiratory tract infections have been reported, usually in the first few weeks of commencing treatment.29 Regular serology tests are not required.

Deucravacitinib, a selective tyrosine kinase 2 inhibitor, has been shown to be more effective than apremilast for treating patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in a head-to-head trial.31 Specifically, patients with involvement of the scalp, nails and/or palms and soles have shown significant improvement in these areas with deucravacitinib therapy.32,33 It is well tolerated in adults with moderate to severe psoriasis.

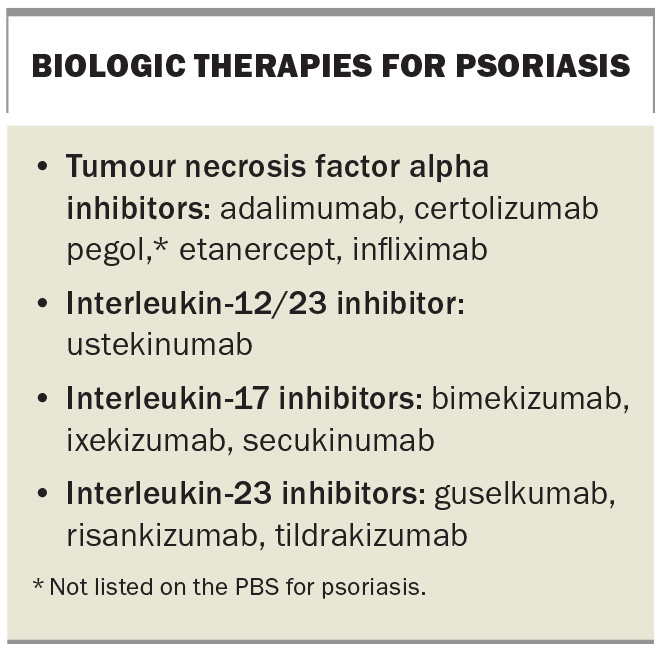

Biologic therapies used to treat psoriasis target the proinflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of the disease: tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukins 12, 17 and 23 (Box).28,34 A Cochrane network meta-analysis at class level showed that biologic therapies were more effective than the nonbiologic systemic agents for moderate to severe psoriasis (living review, updated July 2023).29 Biologic therapies are generally well tolerated. Initial blood tests are required before starting therapy to reduce the risk of reactivating latent infection (tuberculosis, hepatitis B and C infections, strongyloidiasis) and patients should be up-to-date with vaccinations (live vaccines are contraindicated during therapy). Patients may be eligible for treatment with a biologic therapy for severe chronic plaque psoriasis through the PBS if specific criteria are satisfied.28

Outcome

The case patient was diagnosed with severe palmoplantar psoriasis on the basis of the characteristic well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with hyperkeratosis and painful fissures. The presence of nail pitting was consistent with the diagnosis.

His initial management involved a high-potency topical corticosteroid and vitamin D analogue (betamethasone dipropionate 500 mcg/g and calcipotriol 50 mcg/g ointment, at night) and salicylic acid 12% (in the morning). Given his previous history of a failed response to topical therapy alone, he also commenced concurrent hand and foot narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy and methotrexate. In addition, he was counselled about lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation being a key factor for improving his response to treatment. However, he continued to experience persistent symptoms.

After unsuccessful phototherapy and a failed response to methotrexate, the patient satisfied PBS criteria for accessing biologic therapy for severe chronic plaque psoriasis. He commenced treatment with risankizumab, which has shown efficacy for long-term control in patients with moderate-to-severe disease.35

Three months after commencing the biologic therapy, the patient had complete resolution of the fissures on the soles of his feet, as well as significant improvement in the plaques and scaling. MT

COMPETING INTERESTS: None.

References

1. Hainer BL. Dermatophyte infections. Am Fam Physician 2003; 67: 101-108.

2. Segal E, Frenkel M. Dermatophyte infections in environmental contexts. Res Microbiol 2015; 166: 564-569.

3. Seebacher C, Bouchara J-P, Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia 2008; 166: 335-352.

4. Tamimi P, Fattahi M, Firooz A, et al. Recalcitrant dermatophyte infections: identification and risk factors. Int J Dermatol 2024; 63: 1398-1403.

5. Mirali S, Abduelmula A, Mufti A, et al. Drugs associated with the development of palmoplantar keratoderma: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg 2021; 25: 553-554.

6. Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC 3rd. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol 2007; 8: 1-11.

7. Schiller S, Seebode C, Hennies HC, Giehl, Emmert S. Palmoplantar keratoderma (PPK): acquired and genetic causes of a not so rare disease. JDDG: J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2014; 12: 781-788.

8. Thomas BR, O’Toole EA. Diagnosis and management of inherited palmoplantar keratodermas. Acta Derm Venereol 2020; 100: adv00094.

9. Guerra L, Castori M, Didona B, Castiglia D, Zambruno G. Hereditary palmoplantar keratodermas. Part II: syndromic palmoplantar keratodermas – diagnostic algorithm and principles of therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 899-925.

10. Calle Sarmiento PM, Chango Azanza JJ. Dyshidrotic eczema: a common cause of palmar dermatitis. Cureus 2020; 12: e10839.

11. Veien NK. Acute and recurrent vesicular hand dermatitis. Dermatologic Clin 2009; 27: 337-353.

12. Lofgren SM, Warshaw EM. Dyshidrosis: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and therapy. Dermatitis 2006; 17: 165-181.

13. Boch K, Langan EA, Kridin K, Zillikens D, Ludwig RJ, Bieber K. Lichen planus. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8: 737813.

14. Summers YL. Lichen planus: epidemiology, symptoms and treatment. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2015.

15. Alaizari NA, Al-Maweri SA, Al-Shamiri HM, Tarakji B, Shugaa-Addin B. Hepatitis C virus infections in oral lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust Dent J 2016; 61: 282-287.

16. Tétu P, Jachiet M, de Masson A, et al. Chronic graft versus host disease presenting as lichen planus pigmentosus. Bone Marrow Transplant 2018; 53: 1048-1050.

17. Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 723-732.

18. Elston DM. Dermatology images: lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024;

90: 1092-1097.

19. Sontheimer RD. Lichenoid tissue reaction/interface dermatitis: clinical and histological perspectives. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129: 1088-1099.

20. Khandpur S, Singhal V, Sharma VK. Palmoplantar involvement in psoriasis:

a clinical study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011; 77: 625.

21. Stanway A, Oakley A. Psoriasis of the palms and soles. DermNet; 2015. Available online at: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/psoriasis-of-the-palms-and-soles (accessed April 2025).

22. Devjani S, Smith B, Javadi SS, Engel PV, Han G, Wu JJ. Palmoplantar pustulosis: therapy update. J Drugs Dermatol 2024; 23: 626-631.

23. Yan D, Gudjonsson JE, Le S, et al. New frontiers in psoriatic disease research, Part I: genetics, environmental triggers, immunology, pathophysiology, and precision medicine. J Invest Dermatol 2021; 141: 2112-2122.

24. Raposo I, Torres T. Palmoplantar psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: current treatment and future prospects. Am J Clin Dermatol 2016; 17: 349-358.

25. Topical steroids – how much do I use? In: Australian Medicines Handbook. Adelaide SA: AMH; 2017. Available online at: https://resources.amh.net.au/public/fingertipunits.pdf (accessed April 2025).

26. Elmets CA, Korman NJ, Prater EF, et al. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84: 432-470.

27. Lebwohl M, Kircik L, Lacour JP, et al. Twice-weekly topical calcipotriene/betamethasone dipropionate foam as proactive management of plaque psoriasis increases time in remission and is well tolerated over 52 weeks (PSO-LONG trial). J Am Acad Dermatol 2021; 84: 1269-1277.

28. Psoriasis. In: Therapeutic Guidelines. Melbourne: TG; 2022. Available online at: https://tg.org.au (accessed April 2025).

29. Sbidian E, Chaimani A, Garcia-Doval I, et al. Systemic pharmacological treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023; 6: CD011535.

30. Ighani A, Partridge ACR, Shear NH, et al. Comparison of management guidelines for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a review of phototherapy, systemic therapies, and biologic agents. J Cutan Med Surg 2019; 23: 204-221.

31. Strober B, Thaçi D, Sofen H, et al. Deucravacitinib versus placebo and apremilast in moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: Efficacy and safety results from the 52-week, randomized, double-blinded, phase 3 program for evaluation of TYK2 inhibitor psoriasis second trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2023; 88: 40-51.

32. Deucravacitinib for plaque psoriasis. Aust Prescr 2024; 47: 195-196.

33. Kingston P, Blauvelt A, Strober B, et al. Deucravacitinib: a novel TYK2 inhibitor for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis 2023; 8: 156-165.

34. Sanchez IM, Sorenson E, Levin E, et al. The efficacy of biologic therapy for the management of palmoplantar psoriasis and palmoplantar pustulosis: a systematic review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2017; 7: 425-446.

35. Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M, et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2): results from two double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled and ustekinumab-controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2018; 392: 650-661.